![]() What is wickedness? It is that which often many times you have already seen and known in the world. And so often as anything happens that might otherwise trouble you, let this memento presently come to your mind, that it is that which you have already often seen and known.

What is wickedness? It is that which often many times you have already seen and known in the world. And so often as anything happens that might otherwise trouble you, let this memento presently come to your mind, that it is that which you have already often seen and known.

![]() Generally, above and below, you will find but the same things. The very same things that ancient stories, middle age stories, and fresh stories are full of. Towns are full, and houses full. There is nothing that is new. All things that are, are both usual and of little continuance.

Generally, above and below, you will find but the same things. The very same things that ancient stories, middle age stories, and fresh stories are full of. Towns are full, and houses full. There is nothing that is new. All things that are, are both usual and of little continuance.

![]() What fear is there that your dogma or philosophical resolutions and conclusions should become dead in you and lose their proper power and efficacy to make your life happy, as long as those proper and correlative fancies, and representations of things on which they mutually depend (which continually to stir up and revive is in your power) are still kept fresh and alive? It is in my power concerning this thing that is happened, whatever it is, to conceive that which is right and true. If it is, then why am I troubled? Those things that are without my understanding, are nothing to it at all, and that is it only which properly concerns me. Always keep this in mind and you will always be right.

What fear is there that your dogma or philosophical resolutions and conclusions should become dead in you and lose their proper power and efficacy to make your life happy, as long as those proper and correlative fancies, and representations of things on which they mutually depend (which continually to stir up and revive is in your power) are still kept fresh and alive? It is in my power concerning this thing that is happened, whatever it is, to conceive that which is right and true. If it is, then why am I troubled? Those things that are without my understanding, are nothing to it at all, and that is it only which properly concerns me. Always keep this in mind and you will always be right.

![]() That which most men would think themselves most happy with and would prefer before all things, if the gods would grant it to them after their deaths, you may while you live grant to yourself; to live again. See the things of the world again, as you have already seen them. For what else is it to live again?

That which most men would think themselves most happy with and would prefer before all things, if the gods would grant it to them after their deaths, you may while you live grant to yourself; to live again. See the things of the world again, as you have already seen them. For what else is it to live again?

![]() Public shows and solemnities with much pomp and vanity, stage plays, flocks and herds; conflicts and contentions. A bone thrown to a company of hungry curs. A bait for greedy fishes. The painfulness, and continual burden-bearing of wretched ants, the running to and fro of terrified mice.

Public shows and solemnities with much pomp and vanity, stage plays, flocks and herds; conflicts and contentions. A bone thrown to a company of hungry curs. A bait for greedy fishes. The painfulness, and continual burden-bearing of wretched ants, the running to and fro of terrified mice.

![]() Little puppets drawn up and down with wires and nerves: these are the objects of the world, and among all these you must stand steadfast, meekly affected, and free from all manner of indignation, with this right correct thinking and apprehension. That is the worth is of those things which a man affects, so is in very deed every man's worth, more or less.

Little puppets drawn up and down with wires and nerves: these are the objects of the world, and among all these you must stand steadfast, meekly affected, and free from all manner of indignation, with this right correct thinking and apprehension. That is the worth is of those things which a man affects, so is in very deed every man's worth, more or less.

![]() The things that are spoken must be conceived and understood word after word, every one by itself, and so the things that are done, purpose after purpose, every one by itself likewise. And as in matter of purposes and actions, we must presently see what the proper use and relation of every one is, so of words must we be as ready, to consider of every one what is the true meaning, and signification of it according to truth and nature, however it's taken in common use.

The things that are spoken must be conceived and understood word after word, every one by itself, and so the things that are done, purpose after purpose, every one by itself likewise. And as in matter of purposes and actions, we must presently see what the proper use and relation of every one is, so of words must we be as ready, to consider of every one what is the true meaning, and signification of it according to truth and nature, however it's taken in common use.

![]() Is my reason and understanding sufficient for this, or not? If it is sufficient, without any private applause or public ostentation as of an instrument which by nature I am provided, I will make use of it for the work in hand, as of an instrument which by nature I am provided. if it is not, and that otherwise it doesn't belong to me particularly as a private duty, I will either give it over, and leave it to some other that can do it better, or I will endeavor at it, but with the help of some other, who with the joint help of my reason is able to bring something to pass that will now be seasonable and useful for the common good.

Is my reason and understanding sufficient for this, or not? If it is sufficient, without any private applause or public ostentation as of an instrument which by nature I am provided, I will make use of it for the work in hand, as of an instrument which by nature I am provided. if it is not, and that otherwise it doesn't belong to me particularly as a private duty, I will either give it over, and leave it to some other that can do it better, or I will endeavor at it, but with the help of some other, who with the joint help of my reason is able to bring something to pass that will now be seasonable and useful for the common good.

![]() For whatever I do either by myself or with some other, the only thing that I must intend is that it be good and expedient for the public. For as for praise, consider how many who once were much commended, are now already quite forgotten, yes, they that commended them, how even they themselves are long since dead and gone. Don't be ashamed, therefore, whenever you must use the help of others. For whatever it is that lies upon you to change, you must propose it to yourself, as the scaling of walls is to a soldier.

For whatever I do either by myself or with some other, the only thing that I must intend is that it be good and expedient for the public. For as for praise, consider how many who once were much commended, are now already quite forgotten, yes, they that commended them, how even they themselves are long since dead and gone. Don't be ashamed, therefore, whenever you must use the help of others. For whatever it is that lies upon you to change, you must propose it to yourself, as the scaling of walls is to a soldier.

![]() And what if you, through either lameness or some other impediment, are not able to reach to the top of the battlements alone, which with the help of another you may. Will you therefore give it over, or go about it with less courage and alacrity, because you can't do it all alone?

And what if you, through either lameness or some other impediment, are not able to reach to the top of the battlements alone, which with the help of another you may. Will you therefore give it over, or go about it with less courage and alacrity, because you can't do it all alone?

![]() Don't let future things trouble you, for if necessity requires that they come to pass, you will (whenever that is) be provided for them with the same reason by which whatever is now present is made both tolerable and acceptable to you. All things are linked and knitted together, and the knot is sacred, neither is there anything in the world that is not kind and natural in regard of any other thing, or, that has not some kind of reference and natural correspondence with whatever is in the world besides.

Don't let future things trouble you, for if necessity requires that they come to pass, you will (whenever that is) be provided for them with the same reason by which whatever is now present is made both tolerable and acceptable to you. All things are linked and knitted together, and the knot is sacred, neither is there anything in the world that is not kind and natural in regard of any other thing, or, that has not some kind of reference and natural correspondence with whatever is in the world besides.

![]() For all things are ranked together, and by that decency of its due place and order that each particular observes, they all concur together to the making of one and the same cosmos or world. As if you said, a comely piece, or an orderly composition.

For all things are ranked together, and by that decency of its due place and order that each particular observes, they all concur together to the making of one and the same cosmos or world. As if you said, a comely piece, or an orderly composition.

![]() For all things throughout, there is but one order; and through all things, one and the same God, the same substance and the same law. There is one common reason, and one common truth, that belongs to all reasonable creatures, for neither is there save one perfection of all creatures that are of the same kind, and partakers of the same reason.

For all things throughout, there is but one order; and through all things, one and the same God, the same substance and the same law. There is one common reason, and one common truth, that belongs to all reasonable creatures, for neither is there save one perfection of all creatures that are of the same kind, and partakers of the same reason.

![]() Material things soon vanish away into the common substance of the whole; and whatever is formal, or whatever animates that which is material, is soon resumed into the common reason of the whole; and the fame and memory of anything is soon swallowed up by the general age and duration of the whole.

Material things soon vanish away into the common substance of the whole; and whatever is formal, or whatever animates that which is material, is soon resumed into the common reason of the whole; and the fame and memory of anything is soon swallowed up by the general age and duration of the whole.

![]() To a reasonable creature, the same action is both according to nature, and according to reason.

To a reasonable creature, the same action is both according to nature, and according to reason.

![]() Straight of itself, not made straight.

Straight of itself, not made straight.

![]() As several members are united in one body, so are reasonable creatures in a body that is divided and dispersed all made and prepared for one common operation. And this you will apprehend the better if you will use yourself often to say to yourself, I am meloz, or a member of the mass and body of reasonable substances.

As several members are united in one body, so are reasonable creatures in a body that is divided and dispersed all made and prepared for one common operation. And this you will apprehend the better if you will use yourself often to say to yourself, I am meloz, or a member of the mass and body of reasonable substances.

![]() But if you will say I am meroz, or a part, you do not yet love men from your heart. The joy that you take in the exercise of bounty is not yet grounded upon a due rationalization and right apprehension of the nature of things. You exercise it as yet barely upon this ground, as a thing convenient and fitting; not as doing good to yourself when you do good to others.

But if you will say I am meroz, or a part, you do not yet love men from your heart. The joy that you take in the exercise of bounty is not yet grounded upon a due rationalization and right apprehension of the nature of things. You exercise it as yet barely upon this ground, as a thing convenient and fitting; not as doing good to yourself when you do good to others.

![]() Of external things, accidents happen to that which can suffer by external things. Those things that suffer let them complain themselves, if they will. As for me, as long as I don't conceive such a thing, that that which is happened is evil, I have suffered no harm; and it is in my power not to conceive any such thing.

Of external things, accidents happen to that which can suffer by external things. Those things that suffer let them complain themselves, if they will. As for me, as long as I don't conceive such a thing, that that which is happened is evil, I have suffered no harm; and it is in my power not to conceive any such thing.

![]() Whatever any man either does or says, you must be good; not for any man's sake, but for your own nature's sake, as if either gold or the emerald or purple should ever be saying to themselves, "whatever any man either does or says, I must still be an emerald, and I must keep my color."

Whatever any man either does or says, you must be good; not for any man's sake, but for your own nature's sake, as if either gold or the emerald or purple should ever be saying to themselves, "whatever any man either does or says, I must still be an emerald, and I must keep my color."

![]() This will always be my comfort and security: my understanding that rules over all will not of itself bring trouble and vexation upon itself. This I say, it will not put itself in any fear, it will not lead itself into any lust.

This will always be my comfort and security: my understanding that rules over all will not of itself bring trouble and vexation upon itself. This I say, it will not put itself in any fear, it will not lead itself into any lust.

![]() If it is in the power of any other to compel it to fear, or to grieve, it is free for him to use his power. But if it's sure of itself, through some false opinion or supposition incline itself to any such disposition, there is no fear.

If it is in the power of any other to compel it to fear, or to grieve, it is free for him to use his power. But if it's sure of itself, through some false opinion or supposition incline itself to any such disposition, there is no fear.

![]() For as for the body, why should I make the grief of my body to be the grief of my mind? If that itself can either fear or complain, let it. But as for the soul, which indeed, can only be truly sensible of either fear or grief; to which only it belongs according to its different imaginations and opinions, to admit of either of these or of their contraries; you may look to that yourself, that it suffers nothing.

For as for the body, why should I make the grief of my body to be the grief of my mind? If that itself can either fear or complain, let it. But as for the soul, which indeed, can only be truly sensible of either fear or grief; to which only it belongs according to its different imaginations and opinions, to admit of either of these or of their contraries; you may look to that yourself, that it suffers nothing.

![]() Induce her not to any such opinion or persuasion. The understanding is of itself sufficient itself, and needs not (if itself does not bring itself to need) any other thing besides itself, and by consequence as it needs nothing, so neither can it be troubled or hindered by anything, if itself does not trouble and hinder itself.

Induce her not to any such opinion or persuasion. The understanding is of itself sufficient itself, and needs not (if itself does not bring itself to need) any other thing besides itself, and by consequence as it needs nothing, so neither can it be troubled or hindered by anything, if itself does not trouble and hinder itself.

![]() Whatever will fall, falls on what will feel the effects; whoever feels the effects may complain. Unless I think what has happened is evil, and I am not hurt by it, it is in my power to not think it was evil.

Whatever will fall, falls on what will feel the effects; whoever feels the effects may complain. Unless I think what has happened is evil, and I am not hurt by it, it is in my power to not think it was evil.

![]() Is any man so foolish as to fear change, to which all things that once didn't exist owe their being? And what is it that is more pleasing and more familiar to the nature of the universe?

Is any man so foolish as to fear change, to which all things that once didn't exist owe their being? And what is it that is more pleasing and more familiar to the nature of the universe?

![]() How could you use your ordinary hot baths, should not the wood that heated them first be changed? How could you receive any nourishment from those things that you have eaten if they should not be changed? Can anything else that is useful and profitable be created without change?

How could you use your ordinary hot baths, should not the wood that heated them first be changed? How could you receive any nourishment from those things that you have eaten if they should not be changed? Can anything else that is useful and profitable be created without change?

![]() Then how don't you perceive that for you also, by death comes to change, is a thing of the very same nature, and as is necessary for the nature of the universe?

Then how don't you perceive that for you also, by death comes to change, is a thing of the very same nature, and as is necessary for the nature of the universe?

![]() Through the substance of the universe, as through a torrent passes all particular bodies, all being of the same nature, and all joint workers with the universe itself, as in one of our bodies are so many members among themselves. How many such as Chrysippus, how many such as Socrates, how many such as Epictetus, has the age of the world long since swallowed up and devoured?

Through the substance of the universe, as through a torrent passes all particular bodies, all being of the same nature, and all joint workers with the universe itself, as in one of our bodies are so many members among themselves. How many such as Chrysippus, how many such as Socrates, how many such as Epictetus, has the age of the world long since swallowed up and devoured?

![]() Let this, be it either men or businesses, that you have occasion to think of, to the end that your thoughts be not distracted and your mind too earnestly set upon anything, upon every such occasion presently come to your mind. Only one thing will be the object of all my thoughts and cares, that I myself do nothing which to the proper constitution of man (either in regard of the thing itself, or in regard of the manner, or of the time of doing), is contrary.

Let this, be it either men or businesses, that you have occasion to think of, to the end that your thoughts be not distracted and your mind too earnestly set upon anything, upon every such occasion presently come to your mind. Only one thing will be the object of all my thoughts and cares, that I myself do nothing which to the proper constitution of man (either in regard of the thing itself, or in regard of the manner, or of the time of doing), is contrary.

![]() The time when you will have forgotten all things is at hand. And that time is also at hand when you yourself will be forgotten by all. While you are, apply yourself to that especially which to man as he is a man, is most proper and agreeable, and that is for a man even to love them that transgress against him.

The time when you will have forgotten all things is at hand. And that time is also at hand when you yourself will be forgotten by all. While you are, apply yourself to that especially which to man as he is a man, is most proper and agreeable, and that is for a man even to love them that transgress against him.

![]() This shall be, if at the same time that any such thing happens, you should call to mind that they are your kinsmen; that it is through ignorance and against their wills that they sin; and that within a very short while after, both you and he shall be no more. But above all things, that he has not done you any hurt; for that by him your mind and understanding is not made worse or more vile than it was before.

This shall be, if at the same time that any such thing happens, you should call to mind that they are your kinsmen; that it is through ignorance and against their wills that they sin; and that within a very short while after, both you and he shall be no more. But above all things, that he has not done you any hurt; for that by him your mind and understanding is not made worse or more vile than it was before.

![]() The nature of the universe, of the common substance of all things is as it were of so much wax, and has now perchance formed a horse. Then, destroying that figure, has now tempered and fashioned the matter of it into the form and substance of a tree. Then that again into the form and substance of a man, and then that again into some other. Now every one of these does exist but for a very little while.

The nature of the universe, of the common substance of all things is as it were of so much wax, and has now perchance formed a horse. Then, destroying that figure, has now tempered and fashioned the matter of it into the form and substance of a tree. Then that again into the form and substance of a man, and then that again into some other. Now every one of these does exist but for a very little while.

![]() As for dissolution, if it is no grievous thing to the chest or trunk to be joined together, why should it be more grievous to be put asunder?

As for dissolution, if it is no grievous thing to the chest or trunk to be joined together, why should it be more grievous to be put asunder?

![]() An angry countenance is much against nature, and it is often the proper countenance of them that are at the point of death. But were it so that all anger and passion were so thoroughly quenched in you, that it were altogether impossible to kindle it any more, you must not rest satisfied, but further endeavor by good consequence of true reasoning, perfectly to conceive and understand that all anger and passion is against reason.

An angry countenance is much against nature, and it is often the proper countenance of them that are at the point of death. But were it so that all anger and passion were so thoroughly quenched in you, that it were altogether impossible to kindle it any more, you must not rest satisfied, but further endeavor by good consequence of true reasoning, perfectly to conceive and understand that all anger and passion is against reason.

![]() For if you will not be sensible of your innocence; if that also will be gone from you, the comfort of a good conscience that you do everything according to reason. What should you live any longer for?

For if you will not be sensible of your innocence; if that also will be gone from you, the comfort of a good conscience that you do everything according to reason. What should you live any longer for?

![]() All things that now you see are but for a moment. That nature, by which all things in the world are administered, will soon bring change and alteration upon them, and then of their substances make other things like them. Then soon after, others again of the matter and substance of these, that so by these means the world may still appear fresh and new.

All things that now you see are but for a moment. That nature, by which all things in the world are administered, will soon bring change and alteration upon them, and then of their substances make other things like them. Then soon after, others again of the matter and substance of these, that so by these means the world may still appear fresh and new.

![]() Whenever any man trespasses against another, presently consider with yourself what it was that he thought to be good, which was actually, when he trespassed. For when you know this, you will pity him and have no occasion either to wonder, or to be angry.

Whenever any man trespasses against another, presently consider with yourself what it was that he thought to be good, which was actually, when he trespassed. For when you know this, you will pity him and have no occasion either to wonder, or to be angry.

![]() For either you yourself still live in that error and ignorance, as that you supposed either that very thing that he does, or some other like worldly thing, to be good; and so you are bound to pardon him if he has done that which you would have done yourself.

For either you yourself still live in that error and ignorance, as that you supposed either that very thing that he does, or some other like worldly thing, to be good; and so you are bound to pardon him if he has done that which you would have done yourself.

![]() Or if it is that you don't suppose the same things to be good or evil that he does, how can you but be gentle to him, who is in error?

Or if it is that you don't suppose the same things to be good or evil that he does, how can you but be gentle to him, who is in error?

![]() Don't imagine future things as though they were present, but only those that actually are present. Take some aside, so that you take the most benefit from it, and consider of them particularly how badly you would want them if they were not present.

Don't imagine future things as though they were present, but only those that actually are present. Take some aside, so that you take the most benefit from it, and consider of them particularly how badly you would want them if they were not present.

![]() But take heed withal, lest that while you settle your contentment in present things, that in time you grow to prize them too much, as that the want of them (whenever it should fall out) should be a trouble and a vexation to you. Wind up yourself into yourself.

But take heed withal, lest that while you settle your contentment in present things, that in time you grow to prize them too much, as that the want of them (whenever it should fall out) should be a trouble and a vexation to you. Wind up yourself into yourself.

![]() Such is the nature of your reasonable commanding part, as that if it exercises justice, and has by that means tranquility within itself, it rests fully satisfied with itself without any other thing.

Such is the nature of your reasonable commanding part, as that if it exercises justice, and has by that means tranquility within itself, it rests fully satisfied with itself without any other thing.

![]() Wipe off all opinion. Stop the force and violence of unreasonable lusts and affections. Circumscribe the present time, examine whatever it is that happened, either to yourself or to another: divide all present objects, either in that which is formal or material; think of the last hour.

Wipe off all opinion. Stop the force and violence of unreasonable lusts and affections. Circumscribe the present time, examine whatever it is that happened, either to yourself or to another: divide all present objects, either in that which is formal or material; think of the last hour.

![]() That which your neighbor has committed, where the guilt of it lies, there let it rest. Examine in order whatever is spoken. Let your mind penetrate both into the effects and into the causes.

That which your neighbor has committed, where the guilt of it lies, there let it rest. Examine in order whatever is spoken. Let your mind penetrate both into the effects and into the causes.

![]() Rejoice yourself with true simplicity and modesty; and that all middle things between virtue and vice are indifferent to you. Finally, love mankind; obey God.

Rejoice yourself with true simplicity and modesty; and that all middle things between virtue and vice are indifferent to you. Finally, love mankind; obey God.

![]() "All things," he says, "are by certain order and appointment, and of the elements only."

"All things," he says, "are by certain order and appointment, and of the elements only."

![]() It will suffice to remember that all things in general are by a certain order and appointment, if only but a few. And as concerning death, that either dispersion, or the atoms, or annihilation, or extinction, or translation will ensue.

It will suffice to remember that all things in general are by a certain order and appointment, if only but a few. And as concerning death, that either dispersion, or the atoms, or annihilation, or extinction, or translation will ensue.

![]() And as concerning pain, that that which is intolerable is soon ended by death, and that which lasts a long time must be tolerable. And that the mind, in the meantime (which is all in all) may by way of inclusion, or interception, by stopping all manner of commerce and sympathy with the body, still retain its own tranquility.

And as concerning pain, that that which is intolerable is soon ended by death, and that which lasts a long time must be tolerable. And that the mind, in the meantime (which is all in all) may by way of inclusion, or interception, by stopping all manner of commerce and sympathy with the body, still retain its own tranquility.

![]() Your understanding is not made worse by it. As for those parts that suffer, let them, if they can, declare their grief themselves.

Your understanding is not made worse by it. As for those parts that suffer, let them, if they can, declare their grief themselves.

![]() As for praise and commendation, view their mind and understanding, what state they are in; what kind of things they flee from, and what things they seek after: and that as in the seaside, whatever was before to be seen, is by the continual succession of new heaps of sand cast up one upon another, soon hid and covered; so in this life, all former things by those which immediately succeed.

As for praise and commendation, view their mind and understanding, what state they are in; what kind of things they flee from, and what things they seek after: and that as in the seaside, whatever was before to be seen, is by the continual succession of new heaps of sand cast up one upon another, soon hid and covered; so in this life, all former things by those which immediately succeed.

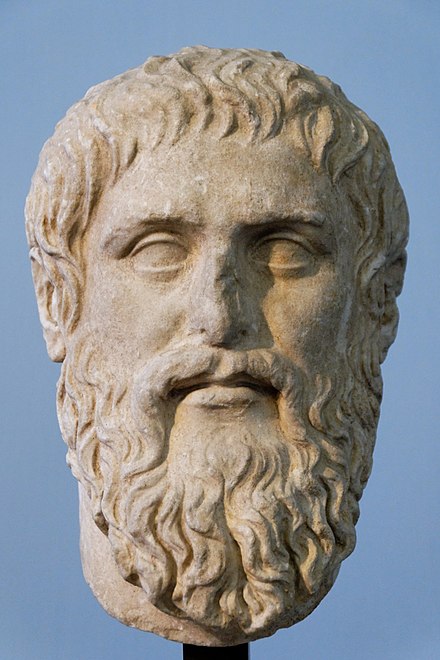

![]() From Plato: "He then whose mind is endowed with true magnanimity, who has accustomed himself to the contemplation both of all times, and of all things in general; can this mortal life (you think) seem any great matter to him? It is not possible, he answered. Then neither will such a one account death a grievous thing? By no means."

From Plato: "He then whose mind is endowed with true magnanimity, who has accustomed himself to the contemplation both of all times, and of all things in general; can this mortal life (you think) seem any great matter to him? It is not possible, he answered. Then neither will such a one account death a grievous thing? By no means."

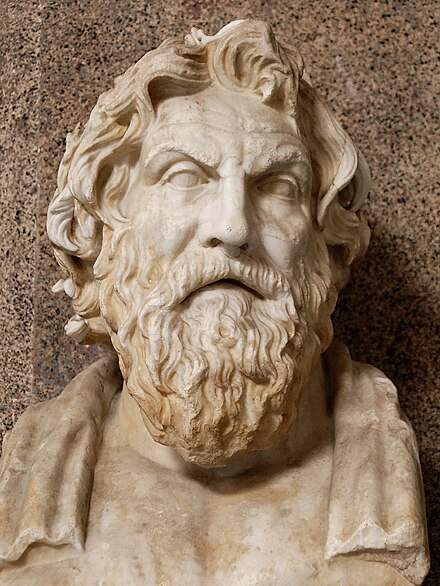

![]() From Antisthenes: "It is a princely thing to do well, and to be ill-spoken of. It is a shameful thing that mind should concern itself with the beauty of the face, not bestow so much care upon itself, as to fashion itself, and to dress itself as best becomes it."

From Antisthenes: "It is a princely thing to do well, and to be ill-spoken of. It is a shameful thing that mind should concern itself with the beauty of the face, not bestow so much care upon itself, as to fashion itself, and to dress itself as best becomes it."

![]() From several poets and comics: "It will avail you but little to turn your anger and indignation upon the things that have befallen you. For as for them, they are not sensible of it. You will only make yourself a laughingstock; both to the gods and to men.

From several poets and comics: "It will avail you but little to turn your anger and indignation upon the things that have befallen you. For as for them, they are not sensible of it. You will only make yourself a laughingstock; both to the gods and to men.

![]() "Our life is reaped like a ripe ear of corn; one is yet standing and another is down. But if it is that I and my children be neglected by the gods, there is some reason even for that. As long as right and equity is of my side, not to lament with them, not to tremble."

"Our life is reaped like a ripe ear of corn; one is yet standing and another is down. But if it is that I and my children be neglected by the gods, there is some reason even for that. As long as right and equity is of my side, not to lament with them, not to tremble."

![]() From Plato: "My answer, full of justice and equity, should be this: your speech is not right, Oh man, if you suppose that he that is of any worth at all should apprehend either life or death as a matter of great hazard and danger; and should not make this rather his only care, to examine his own actions, whether just or unjust: whether actions are of a good, or of a wicked man!

From Plato: "My answer, full of justice and equity, should be this: your speech is not right, Oh man, if you suppose that he that is of any worth at all should apprehend either life or death as a matter of great hazard and danger; and should not make this rather his only care, to examine his own actions, whether just or unjust: whether actions are of a good, or of a wicked man!

![]() "For this case in very truth stands, oh you men of Athens. What place or station a man either has chosen to himself, judging it best for himself; or is by lawful authority put and settled in, therein do I think (all appearance of danger notwithstanding) that he should continue, as one who fears neither death, nor anything else, so much as he fears to commit anything that is vicious and shameful.

"For this case in very truth stands, oh you men of Athens. What place or station a man either has chosen to himself, judging it best for himself; or is by lawful authority put and settled in, therein do I think (all appearance of danger notwithstanding) that he should continue, as one who fears neither death, nor anything else, so much as he fears to commit anything that is vicious and shameful.

![]() "But, Oh noble sir, I pray you consider whether true generosity and true happiness do not consist in something else, rather than in the preservation either of our, or other men's lives. For it is not the part of a man that is a man indeed to desire to live long or to make much of his life while he lives, but rather (he that is such) will in these things wholly refer himself to the gods, and believing that which every woman can tell him, that no man can escape death; the only thing that he takes thought and care for is this, that what time he lives, he may live as well and as virtuously as he can possibly.

"But, Oh noble sir, I pray you consider whether true generosity and true happiness do not consist in something else, rather than in the preservation either of our, or other men's lives. For it is not the part of a man that is a man indeed to desire to live long or to make much of his life while he lives, but rather (he that is such) will in these things wholly refer himself to the gods, and believing that which every woman can tell him, that no man can escape death; the only thing that he takes thought and care for is this, that what time he lives, he may live as well and as virtuously as he can possibly.

![]() "To look about, and with the eyes following the course of the stars and planets as though you would run with them; and to perpetually pay attention to the several changes of the elements, one into another. For such fancies and imaginations help much to purge away the dross and filth of this, our earthly life."

"To look about, and with the eyes following the course of the stars and planets as though you would run with them; and to perpetually pay attention to the several changes of the elements, one into another. For such fancies and imaginations help much to purge away the dross and filth of this, our earthly life."

![]() That also is a fine passage of Plato's, where he speaks of worldly things in these words: "you must also, as from some higher place, look down, as it were, upon the things of this world, as flocks, armies, husbandmen's labors, marriages, divorces, generations, deaths, the tumults of courts and places of adjudications; desert places; the several nations of barbarians, public festivals, mournings, fairs, markets." How all things upon earth are pell mell, and how miraculously things contrary to one to another concur to the beauty and perfection of this universe.

That also is a fine passage of Plato's, where he speaks of worldly things in these words: "you must also, as from some higher place, look down, as it were, upon the things of this world, as flocks, armies, husbandmen's labors, marriages, divorces, generations, deaths, the tumults of courts and places of adjudications; desert places; the several nations of barbarians, public festivals, mournings, fairs, markets." How all things upon earth are pell mell, and how miraculously things contrary to one to another concur to the beauty and perfection of this universe.

![]() Look back on things of former ages, as upon the manifold changes and conversions of several monarchies and commonwealths. We may also foresee future things, for they will all be of the same kind; neither is it possible that they should leave the tune or break the concert that is now begun, as it were, by these things that are now done and brought to pass in the world.

Look back on things of former ages, as upon the manifold changes and conversions of several monarchies and commonwealths. We may also foresee future things, for they will all be of the same kind; neither is it possible that they should leave the tune or break the concert that is now begun, as it were, by these things that are now done and brought to pass in the world.

![]() It comes all to one therefore, whether a man be a spectator of the things of this life but forty years, or whether he sees them ten thousand years together. For what shall he see more? "And as for those parts that came from the earth, they shall return to the earth again; and those that came from heaven, they also shall return to those heavenly places."

It comes all to one therefore, whether a man be a spectator of the things of this life but forty years, or whether he sees them ten thousand years together. For what shall he see more? "And as for those parts that came from the earth, they shall return to the earth again; and those that came from heaven, they also shall return to those heavenly places."

![]() Whether it be a mere dissolution and unbinding of the manifold intricacies and entanglements of the confused atoms; or some such dispersion of the simple and incorruptible elements... "With meats and drinks and diverse charms, they seek to divert the channel, that they might not die. Yet we must need to endure that blast of wind that comes from above, though we toil and labor never so much."

Whether it be a mere dissolution and unbinding of the manifold intricacies and entanglements of the confused atoms; or some such dispersion of the simple and incorruptible elements... "With meats and drinks and diverse charms, they seek to divert the channel, that they might not die. Yet we must need to endure that blast of wind that comes from above, though we toil and labor never so much."

![]() He has a stronger body and is a better wrestler than I. So what? Is he more bountiful? Is he more modest? Does he bear all adverse chances with more equanimity, or with his neighbor's offenses with more meekness and gentleness than I?

He has a stronger body and is a better wrestler than I. So what? Is he more bountiful? Is he more modest? Does he bear all adverse chances with more equanimity, or with his neighbor's offenses with more meekness and gentleness than I?

![]() Where a matter may be agreeably finished by reason, to which both the gods and men is common, there can be no just cause of grief or sorrow. For where the fruit and benefit of an action began and prosecuted according to the proper constitution of man may be reaped and obtained, or is sure and certain, it is against reason that any damage should there be suspected.

Where a matter may be agreeably finished by reason, to which both the gods and men is common, there can be no just cause of grief or sorrow. For where the fruit and benefit of an action began and prosecuted according to the proper constitution of man may be reaped and obtained, or is sure and certain, it is against reason that any damage should there be suspected.

![]() In all places, and at all times, it is in your power to religiously embrace whatever by God's appointment has happened to you, and justly to converse with those men whom you have to deal with, and accurately to examine every fancy that presents itself, that nothing may slip and steal in before you have rightly comprehended the true nature of it.

In all places, and at all times, it is in your power to religiously embrace whatever by God's appointment has happened to you, and justly to converse with those men whom you have to deal with, and accurately to examine every fancy that presents itself, that nothing may slip and steal in before you have rightly comprehended the true nature of it.

![]() Don't look to other men's minds and understandings, but look forward where nature, both of the universe and in those things that happen to you, and you in particular in those things that you do: it leads and direct you. Now, every one is bound to do that which is consequent and agreeable to the end which by his true natural constitution he was ordained to.

Don't look to other men's minds and understandings, but look forward where nature, both of the universe and in those things that happen to you, and you in particular in those things that you do: it leads and direct you. Now, every one is bound to do that which is consequent and agreeable to the end which by his true natural constitution he was ordained to.

![]() As for all other things, they are ordained for the use of reasonable creatures. As in all things we see that that which is worse and inferior, is made for that which is better. Reasonable creatures are ordained one for another. That therefore which is chief in every man's constitution is that he intend the common good.

As for all other things, they are ordained for the use of reasonable creatures. As in all things we see that that which is worse and inferior, is made for that which is better. Reasonable creatures are ordained one for another. That therefore which is chief in every man's constitution is that he intend the common good.

![]() The second is, that he doesn't yield to any lusts and motions of the flesh. For it is the part and privilege of the reasonable and intellectual faculty, that she can so bound herself, so that neither the sensitive, nor the appetitive faculties may not anyways prevail upon her. For both these are brutish.

The second is, that he doesn't yield to any lusts and motions of the flesh. For it is the part and privilege of the reasonable and intellectual faculty, that she can so bound herself, so that neither the sensitive, nor the appetitive faculties may not anyways prevail upon her. For both these are brutish.

![]() And therefore over both she challenges mastery, and if in her right temper cannot endure to be subject to either, anyway. And this is indeed most just. For by nature she was ordained to command all in the body.

And therefore over both she challenges mastery, and if in her right temper cannot endure to be subject to either, anyway. And this is indeed most just. For by nature she was ordained to command all in the body.

![]() The third thing proper to man by his constitution is to avoid all rashness, and not to be subject to error. Then let the mind apply herself and go straight on to these things, then, without any distraction about other things, and she has her end, and by consequent her happiness.

The third thing proper to man by his constitution is to avoid all rashness, and not to be subject to error. Then let the mind apply herself and go straight on to these things, then, without any distraction about other things, and she has her end, and by consequent her happiness.

![]() As one who had lived and were now to die, bestow whatever is yet remaining fully as a gracious surplus on top of a virtuous life. Love and affect that only, whatever it is that happens and is appointed to you by the fates. For what can be more reasonable?

As one who had lived and were now to die, bestow whatever is yet remaining fully as a gracious surplus on top of a virtuous life. Love and affect that only, whatever it is that happens and is appointed to you by the fates. For what can be more reasonable?

![]() And as anything happens to you by way of cross, or calamity, presently call to mind and set before your eyes the examples of some other men to whom the same thing likewise once happened. Well, what did they do? They grieved; they wondered; they complained. And where are they now? All dead and gone. Will you also be like one of them?

And as anything happens to you by way of cross, or calamity, presently call to mind and set before your eyes the examples of some other men to whom the same thing likewise once happened. Well, what did they do? They grieved; they wondered; they complained. And where are they now? All dead and gone. Will you also be like one of them?

![]() Or rather leaving to men of the world (whose life both in regard of themselves, and them that they converse with, is nothing but mere mutability; or men of as fickle minds, as fickle bodies; ever changing and soon changed themselves) let it be your only care and study how to make a correct use of all such accidents. For there is good use to be made of them, and they will prove fit matter for you to work on, if it's both your care and your desire, that whatever you do, you yourself may like and approve yourself for it.

Or rather leaving to men of the world (whose life both in regard of themselves, and them that they converse with, is nothing but mere mutability; or men of as fickle minds, as fickle bodies; ever changing and soon changed themselves) let it be your only care and study how to make a correct use of all such accidents. For there is good use to be made of them, and they will prove fit matter for you to work on, if it's both your care and your desire, that whatever you do, you yourself may like and approve yourself for it.

![]() And both these, see that you remember well, according as the diversity of the matter of the action that you are about shall require. Look within; within is the fountain of all good. Such a fountain, where springing waters can never fail, so you dig still deeper and deeper.

And both these, see that you remember well, according as the diversity of the matter of the action that you are about shall require. Look within; within is the fountain of all good. Such a fountain, where springing waters can never fail, so you dig still deeper and deeper.

![]() You must also use yourself to keep your body fixed and steady; free from all loose, unstable motion or posture. And as on your face and looks, your mind easily has power over them to keep them to that which is grave and decent; so let it challenge the same power over the whole body as well. But also observe all things like that, as that it is without any manner of affectation.

You must also use yourself to keep your body fixed and steady; free from all loose, unstable motion or posture. And as on your face and looks, your mind easily has power over them to keep them to that which is grave and decent; so let it challenge the same power over the whole body as well. But also observe all things like that, as that it is without any manner of affectation.

![]() The art of true living in this world is more like a wrestler's than a dancer's practice. For in this they both agree, to teach a man whatever falls upon him that he may be ready for it, and that nothing may cast him down.

The art of true living in this world is more like a wrestler's than a dancer's practice. For in this they both agree, to teach a man whatever falls upon him that he may be ready for it, and that nothing may cast him down.

![]() You must continually ponder and consider with yourself what manner of men they are, and what is their present state of their minds and understandings, whose good word and testimony you desire. For then neither will you see cause to complain of them that offend against their will, or find any want of their applause, if once you just penetrate into the true force and ground, both of their opinions and of their desires.

You must continually ponder and consider with yourself what manner of men they are, and what is their present state of their minds and understandings, whose good word and testimony you desire. For then neither will you see cause to complain of them that offend against their will, or find any want of their applause, if once you just penetrate into the true force and ground, both of their opinions and of their desires.

![]() "No soul," says he, "is willingly bereft of the truth," and by consequent, neither of justice, or temperance, or kindness, and mildness; nor of anything that is of the same kind. It is most needful that you should always remember this. For if so, you will be far more gentle and moderate towards all men.

"No soul," says he, "is willingly bereft of the truth," and by consequent, neither of justice, or temperance, or kindness, and mildness; nor of anything that is of the same kind. It is most needful that you should always remember this. For if so, you will be far more gentle and moderate towards all men.

![]() Whatever pain you're in, let this presently come to your mind, that it isn't anything you need to be ashamed of, and neither is it a thing where your understanding, that has the government of all, can be made worse. For neither in regard of the substance of it, nor in regard of the end of it (which is, to intend the common good) can it alter and corrupt it.

Whatever pain you're in, let this presently come to your mind, that it isn't anything you need to be ashamed of, and neither is it a thing where your understanding, that has the government of all, can be made worse. For neither in regard of the substance of it, nor in regard of the end of it (which is, to intend the common good) can it alter and corrupt it.

![]() This also of Epicurus may help when you are in the most pain, that it is "neither intolerable, nor eternal" so you keep yourself to the true bounds and limits of reason and not give way to opinion.

This also of Epicurus may help when you are in the most pain, that it is "neither intolerable, nor eternal" so you keep yourself to the true bounds and limits of reason and not give way to opinion.

![]() You also must consider that there are many things which often trouble and vex you insensibly, as not armed against them with patience, because they don't ordinarily go under the name of pains, which in very deed are of the same nature as pain; as to slumber unquietly, to suffer from fever, to want appetite. When, therefore, any of these things make you discontented, check yourself with these words: Now has pain given you the foil. Your courage has failed you.

You also must consider that there are many things which often trouble and vex you insensibly, as not armed against them with patience, because they don't ordinarily go under the name of pains, which in very deed are of the same nature as pain; as to slumber unquietly, to suffer from fever, to want appetite. When, therefore, any of these things make you discontented, check yourself with these words: Now has pain given you the foil. Your courage has failed you.

![]() Take heed lest at any time you stand so affected, though towards unnatural evil men, as ordinary men are commonly towards one another.

Take heed lest at any time you stand so affected, though towards unnatural evil men, as ordinary men are commonly towards one another.

![]() How do we know whether Socrates was so eminent indeed, and of so extraordinary a disposition? For that he died more gloriously, that he disputed with the Sophists more subtly, that he watched in the frost more assiduously, that being commanded to fetch innocent Salaminius, he refused to do it more generously? All this will not serve.

How do we know whether Socrates was so eminent indeed, and of so extraordinary a disposition? For that he died more gloriously, that he disputed with the Sophists more subtly, that he watched in the frost more assiduously, that being commanded to fetch innocent Salaminius, he refused to do it more generously? All this will not serve.

![]() Nor that he walked in the streets, with much gravity and majesty, as was objected to him by his adversaries, which nevertheless a man may well doubt of, whether it were so or not, or, which above all the rest, if so be that it were true, a man would well consider whether commendable, or dis-commendable. The thing therefore that we must inquire into is this: what manner of soul Socrates had. Whether his disposition was such that all that he stood upon, and sought after in this world, was barely this, that he might ever carry himself justly towards men, and in holiness towards the gods.

Nor that he walked in the streets, with much gravity and majesty, as was objected to him by his adversaries, which nevertheless a man may well doubt of, whether it were so or not, or, which above all the rest, if so be that it were true, a man would well consider whether commendable, or dis-commendable. The thing therefore that we must inquire into is this: what manner of soul Socrates had. Whether his disposition was such that all that he stood upon, and sought after in this world, was barely this, that he might ever carry himself justly towards men, and in holiness towards the gods.

![]() Neither vexing himself to no purpose at the wickedness of others, nor yet ever condescending to any man's evil fact, or evil intentions, through either fear, or engagement of friendship. Whether of those things that happened to him by God's appointment, he neither wondered at any when it happened, or thought it intolerable in the trial of it.

Neither vexing himself to no purpose at the wickedness of others, nor yet ever condescending to any man's evil fact, or evil intentions, through either fear, or engagement of friendship. Whether of those things that happened to him by God's appointment, he neither wondered at any when it happened, or thought it intolerable in the trial of it.

![]() And lastly, whether he never did suffer his mind to sympathize with the senses, and affections of the body. For we must not think that nature has so mixed and tempered it with the body, as that she doesn't have the power to circumscribe herself, and by herself to intend her own ends and occasions.

And lastly, whether he never did suffer his mind to sympathize with the senses, and affections of the body. For we must not think that nature has so mixed and tempered it with the body, as that she doesn't have the power to circumscribe herself, and by herself to intend her own ends and occasions.

![]() It is very possible that a man could be a very divine man and yet be altogether unknown. This you must ever be mindful of, as of this also, that a man's true happiness consists in very few things. And that although you despair that you will ever be a good either logician, or naturalist, you are never the further off by it from being either liberal, or modest, or charitable, or obedient to God.

It is very possible that a man could be a very divine man and yet be altogether unknown. This you must ever be mindful of, as of this also, that a man's true happiness consists in very few things. And that although you despair that you will ever be a good either logician, or naturalist, you are never the further off by it from being either liberal, or modest, or charitable, or obedient to God.

![]() You may run out your time free from all compulsion in all cheerfulness and alacrity, though men should exclaim against you not so much, and the wild beasts should pull asunder the poor members of your pampered mass of flesh.

You may run out your time free from all compulsion in all cheerfulness and alacrity, though men should exclaim against you not so much, and the wild beasts should pull asunder the poor members of your pampered mass of flesh.

![]() For what in either of these or the like cases should hinder the mind to retain her own rest and tranquility, consisting both in the right judgment of those things that happen to her, and in the ready use of all present matters and occasions? So that her judgment may say, to that which is befallen her by way of cross: this you are indeed, and according to your true nature; notwithstanding that in the judgment of opinion you appear otherwise, and her discretion to the present object you are that which I sought.

For what in either of these or the like cases should hinder the mind to retain her own rest and tranquility, consisting both in the right judgment of those things that happen to her, and in the ready use of all present matters and occasions? So that her judgment may say, to that which is befallen her by way of cross: this you are indeed, and according to your true nature; notwithstanding that in the judgment of opinion you appear otherwise, and her discretion to the present object you are that which I sought.

![]() For whatever it is that is now present I shall ever embrace as a fit and seasonable object, both for my reasonable faculty and for my sociable or charitable inclination to work on.

For whatever it is that is now present I shall ever embrace as a fit and seasonable object, both for my reasonable faculty and for my sociable or charitable inclination to work on.

![]() And that which is principal in this matter, is that it may be referred either to the praise of God, or to the good of men. For either to God or to man, whatever it is that happens in the world has in the ordinary course of nature its proper reference; neither is there anything that in regard of nature is either new, or reluctant and intractable, but all things both usual and easy.

And that which is principal in this matter, is that it may be referred either to the praise of God, or to the good of men. For either to God or to man, whatever it is that happens in the world has in the ordinary course of nature its proper reference; neither is there anything that in regard of nature is either new, or reluctant and intractable, but all things both usual and easy.

![]() A man has attained the state of perfection in his life and conversation when he so spends every day as if it were his last day, never hot and vehement in his affections, nor yet so cold and stupid as one that had no sense, and is free from all manner of dissimulation.

A man has attained the state of perfection in his life and conversation when he so spends every day as if it were his last day, never hot and vehement in his affections, nor yet so cold and stupid as one that had no sense, and is free from all manner of dissimulation.

![]() Can the gods, who are immortal for the continuance of so many ages bear without indignation with such and so many sinners as have ever been, yes not only so, but also take such care for them that they want nothing; and do you so grievously take on as one that could bear with them no longer; you that only exist for a moment in time?

Can the gods, who are immortal for the continuance of so many ages bear without indignation with such and so many sinners as have ever been, yes not only so, but also take such care for them that they want nothing; and do you so grievously take on as one that could bear with them no longer; you that only exist for a moment in time?

![]() Yes, you that are one of those sinners yourself? A very ridiculous thing it is, that any man should dispense with vice and wickedness in himself, which is in his power to restrain, and should go about to suppress it in others, which is altogether impossible.

Yes, you that are one of those sinners yourself? A very ridiculous thing it is, that any man should dispense with vice and wickedness in himself, which is in his power to restrain, and should go about to suppress it in others, which is altogether impossible.

![]() Whatever object our reasonable and sociable faculty meets with that affords nothing either for the satisfaction of reason, or for the practice of charity, she worthily thinks unworthy of herself.

Whatever object our reasonable and sociable faculty meets with that affords nothing either for the satisfaction of reason, or for the practice of charity, she worthily thinks unworthy of herself.

![]() When you have done well and another is benefited by your action, you must look like a fool if you look for a third thing besides, as that it may appear to others that you have done well, or that you may in time receive one good turn for another? No man used to be weary of that which is beneficial to him. But every action that is according to nature is beneficial. Then don't be weary of doing that which is beneficial to yourself while it is as well to others.

When you have done well and another is benefited by your action, you must look like a fool if you look for a third thing besides, as that it may appear to others that you have done well, or that you may in time receive one good turn for another? No man used to be weary of that which is beneficial to him. But every action that is according to nature is beneficial. Then don't be weary of doing that which is beneficial to yourself while it is as well to others.

![]() The nature of the universe certainly did once before it was created whatever it has done since, deliberate and so resolve upon the creation of the world. Now since that time, whatever it is that is and happens in the world is either only a consequence of that one and first deliberation, or if it is that this ruling rational part of the world takes any thought and care of particular things, they are surely his reasonable and principal creatures that are the proper object of his particular care and providence. This often thought upon, is very conducive to your tranquility.

The nature of the universe certainly did once before it was created whatever it has done since, deliberate and so resolve upon the creation of the world. Now since that time, whatever it is that is and happens in the world is either only a consequence of that one and first deliberation, or if it is that this ruling rational part of the world takes any thought and care of particular things, they are surely his reasonable and principal creatures that are the proper object of his particular care and providence. This often thought upon, is very conducive to your tranquility.

| Chapter 6 | Chapter 8 |