![]() The matter the universe consists of is of itself very tractable and pliable. That rational essence that governs it has in itself no cause to do evil. It has no evil in itself, and can't do anything that is evil. Neither can anything be hurt by it. And all things are done and determined according to its will and prescript.

The matter the universe consists of is of itself very tractable and pliable. That rational essence that governs it has in itself no cause to do evil. It has no evil in itself, and can't do anything that is evil. Neither can anything be hurt by it. And all things are done and determined according to its will and prescript.

![]() Make it all the same to you that whether you're half frozen or well warm, whether only napping, or after a full sleep, whether scolded or commended, do your duty. Whether dying or doing something else, for that also, "to die," must among the rest be reckoned as one of the duties and actions of our lives.

Make it all the same to you that whether you're half frozen or well warm, whether only napping, or after a full sleep, whether scolded or commended, do your duty. Whether dying or doing something else, for that also, "to die," must among the rest be reckoned as one of the duties and actions of our lives.

![]() Look in, and don't let either the proper quality or the true worth of anything pass you before you fully comprehend it.

Look in, and don't let either the proper quality or the true worth of anything pass you before you fully comprehend it.

![]() All substances soon change, and either they shall be resolved by way of exhalation (if so be that all things shall be reunited into one substance), or as others maintain, they shall be scattered and dispersed.

All substances soon change, and either they shall be resolved by way of exhalation (if so be that all things shall be reunited into one substance), or as others maintain, they shall be scattered and dispersed.

![]() As for that Rational Essence by which all things are governed, as it best understands itself, both its own disposition, and what it does, and what matter it has to do with and accordingly does everything. So we that don't wonder, if we wonder at many things, the reasons of which we cannot comprehend.

As for that Rational Essence by which all things are governed, as it best understands itself, both its own disposition, and what it does, and what matter it has to do with and accordingly does everything. So we that don't wonder, if we wonder at many things, the reasons of which we cannot comprehend.

![]() The best kind of revenge is to not to become like them.

The best kind of revenge is to not to become like them.

![]() Let this be your only joy and your only comfort, from one sociable kind action without intermission to pass to another, God being ever in your mind.

Let this be your only joy and your only comfort, from one sociable kind action without intermission to pass to another, God being ever in your mind.

![]() The rational commanding part, as it alone can stir up and turn itself, so it makes both itself to be, and everything that happens, to appear to itself as it wills itself.

The rational commanding part, as it alone can stir up and turn itself, so it makes both itself to be, and everything that happens, to appear to itself as it wills itself.

![]() According to the nature of the universe, all particular things are not determined according to any other nature, either about compassing and containing; or within, dispersed and contained; or without, depending. Either this universe is a mere confused mass, and an intricate context of things, which shall in time be scattered and dispersed again, or it is a union consisting of order, and administered by Providence.

According to the nature of the universe, all particular things are not determined according to any other nature, either about compassing and containing; or within, dispersed and contained; or without, depending. Either this universe is a mere confused mass, and an intricate context of things, which shall in time be scattered and dispersed again, or it is a union consisting of order, and administered by Providence.

![]() If the first, why should I desire to continue any longer in this random confusion and co-mixing or blending substances that don't come from the same places? Or why should I care about anything else, since that as soon as it might be, I may be earth again? And why should I trouble myself any more while I seek to please the gods?

If the first, why should I desire to continue any longer in this random confusion and co-mixing or blending substances that don't come from the same places? Or why should I care about anything else, since that as soon as it might be, I may be earth again? And why should I trouble myself any more while I seek to please the gods?

![]() Whatever I do, dispersion is my end, and will come upon me whether I will or not. But if the latter is, then I am not religious in vain; then I will be quiet and patient, and put my trust in Him, who is the Governor of all.

Whatever I do, dispersion is my end, and will come upon me whether I will or not. But if the latter is, then I am not religious in vain; then I will be quiet and patient, and put my trust in Him, who is the Governor of all.

![]() Whenever by some hard occurrences you are constrained to be troubled and vexed, return to yourself as soon as you may, and not be out of tune longer than you need to be. That way you will be better able to keep your part another time, and to maintain the harmony, if you use yourself to this continually; once out, presently to have recourse to it, and to begin again.

Whenever by some hard occurrences you are constrained to be troubled and vexed, return to yourself as soon as you may, and not be out of tune longer than you need to be. That way you will be better able to keep your part another time, and to maintain the harmony, if you use yourself to this continually; once out, presently to have recourse to it, and to begin again.

![]() If you had both a stepmother and a living natural mother, you would honor and respect her also; nevertheless to your own natural mother would you seek refuge, and her recourse would be continual.

If you had both a stepmother and a living natural mother, you would honor and respect her also; nevertheless to your own natural mother would you seek refuge, and her recourse would be continual.

![]() So let the court and your philosophy be to you. Have recourse to it often, and comfort yourself in her, by whom it is that those other things are made tolerable to you, and you also in those things not intolerable to others.

So let the court and your philosophy be to you. Have recourse to it often, and comfort yourself in her, by whom it is that those other things are made tolerable to you, and you also in those things not intolerable to others.

![]() How marvelously useful it is for a man to give himself meats, and all such things that are for the mouth, under a right apprehension and imagination! For example: This is the carcass of a fish; this of a bird; and this of a hog. And again more generally; this syrup, this excellent highly commended wine, is but the bare juice of an ordinary grape. This purple robe, but sheep's hairs, dyed with the blood of a shellfish.

How marvelously useful it is for a man to give himself meats, and all such things that are for the mouth, under a right apprehension and imagination! For example: This is the carcass of a fish; this of a bird; and this of a hog. And again more generally; this syrup, this excellent highly commended wine, is but the bare juice of an ordinary grape. This purple robe, but sheep's hairs, dyed with the blood of a shellfish.

![]() So for coitus, it is but the attrition of an ordinary base entrails, and the excretion of a little vile snot, with a certain kind of convulsion, according to Hippocrates; his opinion. How excellent useful are these lively fancies and representations of things, thus penetrating and passing through the objects, to make their true nature known and apparent!

So for coitus, it is but the attrition of an ordinary base entrails, and the excretion of a little vile snot, with a certain kind of convulsion, according to Hippocrates; his opinion. How excellent useful are these lively fancies and representations of things, thus penetrating and passing through the objects, to make their true nature known and apparent!

![]() You must use this all your life long, and upon all occasions: and then specially, when matters are apprehended as of great worth and respect, your care must be to uncover them, and to behold their vileness, and to take away from them all those serious circumstances and expressions under which they made so grave a show. For outward pomp and appearance is a great juggler; and then especially are you in danger of being beguiled by it the most, when (to a man's thinking) you seem to be most employed about matters of moment.

You must use this all your life long, and upon all occasions: and then specially, when matters are apprehended as of great worth and respect, your care must be to uncover them, and to behold their vileness, and to take away from them all those serious circumstances and expressions under which they made so grave a show. For outward pomp and appearance is a great juggler; and then especially are you in danger of being beguiled by it the most, when (to a man's thinking) you seem to be most employed about matters of moment.

![]() See what Crates11 says concerning Xenocrates himself11.

See what Crates11 says concerning Xenocrates himself11.

![]() Those things which the common sort of people admire are, most of them, such things as are very general, and may be comprehended under things merely natural or naturally affected and qualified, as stones, wood, figs, vines, olives.

Those things which the common sort of people admire are, most of them, such things as are very general, and may be comprehended under things merely natural or naturally affected and qualified, as stones, wood, figs, vines, olives.

![]() Those that are admired by the more moderate and restrained, are comprehended under things animated, as flocks and herds. Those that are yet more gentle and curious, their admiration is commonly confined to reasonable creatures only. Not in general as they are reasonable, but as they are capable of are, or of some craft and subtle invention. Perchance to barely be reasonable creatures, as they that delight in the possession of many slaves.

Those that are admired by the more moderate and restrained, are comprehended under things animated, as flocks and herds. Those that are yet more gentle and curious, their admiration is commonly confined to reasonable creatures only. Not in general as they are reasonable, but as they are capable of are, or of some craft and subtle invention. Perchance to barely be reasonable creatures, as they that delight in the possession of many slaves.

![]() But he that honors a reasonable soul in general, as it is reasonable and naturally sociable, little regards anything else, and above all things is careful to preserve his own, in the continual habit and exercise both of reason and sociableness. Thereby cooperates with him of whose nature he also participates; God.

But he that honors a reasonable soul in general, as it is reasonable and naturally sociable, little regards anything else, and above all things is careful to preserve his own, in the continual habit and exercise both of reason and sociableness. Thereby cooperates with him of whose nature he also participates; God.

![]() Some things are in a hurry to exist, and others to exist no more. And even whatever now is, some part of it has already perished. Perpetual fluxes and alterations renew the world, as the perpetual course of time makes the age of the world (of itself infinite2) to appear always fresh and new.

Some things are in a hurry to exist, and others to exist no more. And even whatever now is, some part of it has already perished. Perpetual fluxes and alterations renew the world, as the perpetual course of time makes the age of the world (of itself infinite2) to appear always fresh and new.

![]() In such a flux and course of all things, what of these things that any man should regard goes away so fast, since among all there is not any that a man may fasten and fix upon?

In such a flux and course of all things, what of these things that any man should regard goes away so fast, since among all there is not any that a man may fasten and fix upon?

![]() As if a man would settle his affection upon some ordinary sparrow living by him, who is no sooner seen, than out of sight. For we must not think otherwise of our lives, than as a mere exhalation of blood, or of an ordinary respiration of air.

As if a man would settle his affection upon some ordinary sparrow living by him, who is no sooner seen, than out of sight. For we must not think otherwise of our lives, than as a mere exhalation of blood, or of an ordinary respiration of air.

![]() For what in our common apprehension is, to breathe in the air and to breathe it out again, which we do daily. So much it is and no more, at once to breathe out all your respiratory faculties into that common air from where but lately (as being but from yesterday, and today), you first breathed it in, and with it, life.

For what in our common apprehension is, to breathe in the air and to breathe it out again, which we do daily. So much it is and no more, at once to breathe out all your respiratory faculties into that common air from where but lately (as being but from yesterday, and today), you first breathed it in, and with it, life.

![]() It is surely not vegetative spiration, which plants have, that in this life should be so dear to us; nor sensitive respiration, the proper life of beasts, both tame and wild; nor this our imaginative faculty; nor that we are subject to be led and carried up and down by the strength of our sensual appetites; or that we can gather, and live together; or that we can feed: for that in effect is no better than that we can defecate.

It is surely not vegetative spiration, which plants have, that in this life should be so dear to us; nor sensitive respiration, the proper life of beasts, both tame and wild; nor this our imaginative faculty; nor that we are subject to be led and carried up and down by the strength of our sensual appetites; or that we can gather, and live together; or that we can feed: for that in effect is no better than that we can defecate.

![]() What is it, then, that should be dear to us? To hear a clattering noise? If not that, then neither is it to be applauded by the tongues of men. For the praises of many tongues, is in effect no better than the clattering of so many tongues. If it's not applause, what is there remaining that should be dear to you?

What is it, then, that should be dear to us? To hear a clattering noise? If not that, then neither is it to be applauded by the tongues of men. For the praises of many tongues, is in effect no better than the clattering of so many tongues. If it's not applause, what is there remaining that should be dear to you?

![]() This is what I think: that in all your motions and actions you are moved, and restrained according to your own true natural constitution and construction only. And to this even ordinary arts and professions lead us. For it is that which every art aims at, that whatever it is, that is by effected and prepared, may be fit for that work that it is prepared for.

This is what I think: that in all your motions and actions you are moved, and restrained according to your own true natural constitution and construction only. And to this even ordinary arts and professions lead us. For it is that which every art aims at, that whatever it is, that is by effected and prepared, may be fit for that work that it is prepared for.

![]() This is the end that he that dresses the vine, and he that takes upon himself either to tame colts, or to train dogs, aims at. What else does the education of children, and all learned professions tend to? Certainly then it is that, which should be dear to us also.

This is the end that he that dresses the vine, and he that takes upon himself either to tame colts, or to train dogs, aims at. What else does the education of children, and all learned professions tend to? Certainly then it is that, which should be dear to us also.

![]() If in this particular it goes well with you, don't care about obtaining other things. But isn't it so, that you can't help but respect other things, too? Then can you truly be free? Then you can't have self-content. Then you will ever be subject to passions.

If in this particular it goes well with you, don't care about obtaining other things. But isn't it so, that you can't help but respect other things, too? Then can you truly be free? Then you can't have self-content. Then you will ever be subject to passions.

![]() For it is not possible, but that you must be envious, and jealous, and suspicious of them whom you know can bereave you of such things; and again, a secret underminer of them, whom you see in present possession of that which is dear to you.

For it is not possible, but that you must be envious, and jealous, and suspicious of them whom you know can bereave you of such things; and again, a secret underminer of them, whom you see in present possession of that which is dear to you.

![]() In short, he must of necessity be full of confusion within himself, and often accuse the gods, whosoever stands in need of these things. But if you will honor and respect your mind only, that will make you acceptable towards yourself, towards your friends very tractable; and conformable and concordant with the gods; that is, accepting with praises whatever they shall think good to appoint and give to you.

In short, he must of necessity be full of confusion within himself, and often accuse the gods, whosoever stands in need of these things. But if you will honor and respect your mind only, that will make you acceptable towards yourself, towards your friends very tractable; and conformable and concordant with the gods; that is, accepting with praises whatever they shall think good to appoint and give to you.

![]() Under, above, and about, are the motions of the elements; but the motion of virtue is none of those motions, but is somewhat more excellent and divine. Whose way (to speed and prosper in it) must be through a way that is not easily comprehended.

Under, above, and about, are the motions of the elements; but the motion of virtue is none of those motions, but is somewhat more excellent and divine. Whose way (to speed and prosper in it) must be through a way that is not easily comprehended.

![]() Who can choose but wonder at them? They will not speak well of them that are at the same time with them, and live with them; yet they themselves are very ambitious, that they that shall follow whom they have never seen, nor shall ever see, should speak well of them. As if a man should grieve that he has not been commended by them who lived before him.

Who can choose but wonder at them? They will not speak well of them that are at the same time with them, and live with them; yet they themselves are very ambitious, that they that shall follow whom they have never seen, nor shall ever see, should speak well of them. As if a man should grieve that he has not been commended by them who lived before him.

![]() Never conceive anything impossible to a man that you can't do, or not without much difficulty do; but whatever in general you can conceive possible and proper to any man, think that very possible to you as well.

Never conceive anything impossible to a man that you can't do, or not without much difficulty do; but whatever in general you can conceive possible and proper to any man, think that very possible to you as well.

![]() Suppose that at the wrestling school somebody has torn you with his nails and broken your head. Well, you are wounded. Yet you don't exclaim; you are not offended with him. You do not suspect him for it afterwards, as one who looks to do you mischief.

Suppose that at the wrestling school somebody has torn you with his nails and broken your head. Well, you are wounded. Yet you don't exclaim; you are not offended with him. You do not suspect him for it afterwards, as one who looks to do you mischief.

![]() Yet even then, though you did your best to save yourself from him, but not from him as an enemy. It is not by way of any suspicious indignation, but by way of gentle and friendly declination. Keep the same mind and disposition in other parts of your life also.

Yet even then, though you did your best to save yourself from him, but not from him as an enemy. It is not by way of any suspicious indignation, but by way of gentle and friendly declination. Keep the same mind and disposition in other parts of your life also.

![]() For there are many things that we must conceive of and comprehend, as though we had had to do with an antagonist at the wrestling school. For as I said, it is very possible for us to avoid and decline, though we neither suspect, nor hate.

For there are many things that we must conceive of and comprehend, as though we had had to do with an antagonist at the wrestling school. For as I said, it is very possible for us to avoid and decline, though we neither suspect, nor hate.

![]() If anyone should reprove me, and make it apparent to me that in any either opinion or action of mine I err, I will most gladly retract it. For it is the truth that I seek after, by which I am sure that no man was hurt; and just as sure, that he who is hurt is one that continues in any error or ignorance whatever.

If anyone should reprove me, and make it apparent to me that in any either opinion or action of mine I err, I will most gladly retract it. For it is the truth that I seek after, by which I am sure that no man was hurt; and just as sure, that he who is hurt is one that continues in any error or ignorance whatever.

![]() I, for my part, will do what belongs to me. As for other things, whether things insensible or things irrational, or if rational, yet deceived and ignorant of the true way, they shall not trouble or distract me.

I, for my part, will do what belongs to me. As for other things, whether things insensible or things irrational, or if rational, yet deceived and ignorant of the true way, they shall not trouble or distract me.

![]() For as for those creatures which are not endued with reason and all other things, and matters of the world whatever, I freely and generously make use of them.

For as for those creatures which are not endued with reason and all other things, and matters of the world whatever, I freely and generously make use of them.

![]() And as for men, towards them as naturally partakers of the same reason, my care is to carry myself sociably. But whatever it is that you are about, remember to call on the gods. And as for the time how long you will live to do these things, let it be altogether indifferent to you, for even three such hours are sufficient.

And as for men, towards them as naturally partakers of the same reason, my care is to carry myself sociably. But whatever it is that you are about, remember to call on the gods. And as for the time how long you will live to do these things, let it be altogether indifferent to you, for even three such hours are sufficient.

![]() Alexander of Macedon, and he that dressed his mules, when once dead both came to one. For either they were both resumed into those original rational essences from whence all things in the world are propagated; or both after one fashion were scattered into atoms.

Alexander of Macedon, and he that dressed his mules, when once dead both came to one. For either they were both resumed into those original rational essences from whence all things in the world are propagated; or both after one fashion were scattered into atoms.

![]() Consider how many different things, whether they concern our bodies or our souls, in a moment of time come to pass in every one of us. You will not wonder if many more things or rather all things that are done can at one time subsist, and coexist in that both one and general, which we call the world.

Consider how many different things, whether they concern our bodies or our souls, in a moment of time come to pass in every one of us. You will not wonder if many more things or rather all things that are done can at one time subsist, and coexist in that both one and general, which we call the world.

![]() If anyone should ask you how the word "Antoninus" is written, would you not quickly fix your attention to it, and utter out in order every letter of it? And if any shall begin to gainsay you and quarrel with you about it, will you quarrel with him again, or rather go on meekly as you had begun, until you have numbered out every letter?

If anyone should ask you how the word "Antoninus" is written, would you not quickly fix your attention to it, and utter out in order every letter of it? And if any shall begin to gainsay you and quarrel with you about it, will you quarrel with him again, or rather go on meekly as you had begun, until you have numbered out every letter?

![]() Then likewise remember that every duty that belongs to a man consists of some certain letters or numbers, as it were, to which keeping yourself without any noise or tumult you must proceed in an orderly manner to your proposed end, forbearing to quarrel with him that would quarrel and fall out with you.

Then likewise remember that every duty that belongs to a man consists of some certain letters or numbers, as it were, to which keeping yourself without any noise or tumult you must proceed in an orderly manner to your proposed end, forbearing to quarrel with him that would quarrel and fall out with you.

![]() Isn't it a cruel thing to forbid men to do those things which they conceive to agree best with their own natures, and to tend most to their own proper good as it behooves them? But you, after a sort, deny them this liberty as often as you are angry with them for their misbehavior.

Isn't it a cruel thing to forbid men to do those things which they conceive to agree best with their own natures, and to tend most to their own proper good as it behooves them? But you, after a sort, deny them this liberty as often as you are angry with them for their misbehavior.

![]() For surely they are led to those sins, whatever they are, as to their proper good and commodity. But it is not so, although you may object. You should therefore teach them better, and make it appear to them, but not be angry with them.

For surely they are led to those sins, whatever they are, as to their proper good and commodity. But it is not so, although you may object. You should therefore teach them better, and make it appear to them, but not be angry with them.

![]() Death is a cessation from the impression of the senses, the tyranny of the passions, the errors of the mind, and the servitude of the body.

Death is a cessation from the impression of the senses, the tyranny of the passions, the errors of the mind, and the servitude of the body.

![]() If in this kind of life your body is able to hold out, it would be a shame if your soul should faint first, and give over. Take heed, lest in time you become a mere Caesar of a philosopher, and receive a new tincture from the court. For it may happen if you don't take heed.

If in this kind of life your body is able to hold out, it would be a shame if your soul should faint first, and give over. Take heed, lest in time you become a mere Caesar of a philosopher, and receive a new tincture from the court. For it may happen if you don't take heed.

![]() Therefore, keep yourself truly simple, good, sincere, grave, free from all ostentation, a lover of that which is just, religious, kind, tender hearted, strong and vigorous, to undergo anything that becomes you. Endeavor to continue such, as philosophy (had you wholly and constantly applied yourself to it) would have made, and secured you.

Therefore, keep yourself truly simple, good, sincere, grave, free from all ostentation, a lover of that which is just, religious, kind, tender hearted, strong and vigorous, to undergo anything that becomes you. Endeavor to continue such, as philosophy (had you wholly and constantly applied yourself to it) would have made, and secured you.

![]() Worship the gods, procure the welfare of men; this life is short. Charitable actions, and a holy disposition, is the only fruit of this earthly life.

Worship the gods, procure the welfare of men; this life is short. Charitable actions, and a holy disposition, is the only fruit of this earthly life.

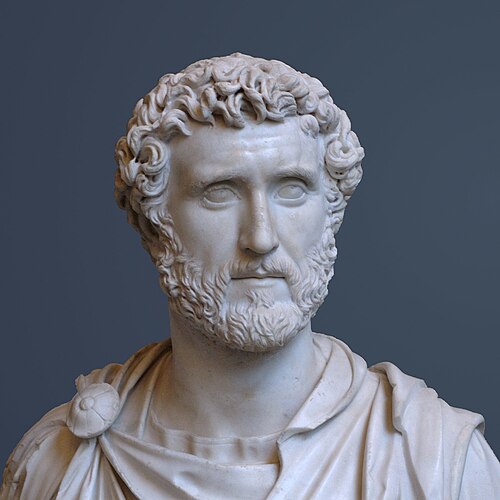

![]() Do all things as become the disciple of Antoninus Pius13. Remember his resolute constancy in things that he did according to reason, his equability in all things, his sanctity. The cheerfulness of his countenance, his sweetness, and how free he was from all vanity. How careful to come to the true and exact knowledge of matters in hand, and how he would by no means give over till he fully understood, and plainly understand the whole state of the business; and how patiently, and without any argument he would bear with those who unjustly condemn him. How he would never be over heavy in anything, nor give ear to slanders and false accusations, but examine and observe with best diligence the several actions and dispositions of men.

Do all things as become the disciple of Antoninus Pius13. Remember his resolute constancy in things that he did according to reason, his equability in all things, his sanctity. The cheerfulness of his countenance, his sweetness, and how free he was from all vanity. How careful to come to the true and exact knowledge of matters in hand, and how he would by no means give over till he fully understood, and plainly understand the whole state of the business; and how patiently, and without any argument he would bear with those who unjustly condemn him. How he would never be over heavy in anything, nor give ear to slanders and false accusations, but examine and observe with best diligence the several actions and dispositions of men.

![]() Again, how he was no backbiter, nor easily frightened, nor suspicious. In his language he was free from all affectation and curiosity, and how easily he would content himself with few things, as lodging, bedding, clothing, and ordinary nourishment, and attendance.

Again, how he was no backbiter, nor easily frightened, nor suspicious. In his language he was free from all affectation and curiosity, and how easily he would content himself with few things, as lodging, bedding, clothing, and ordinary nourishment, and attendance.

![]() How able he was to endure labor, how patient. Able through his spare diet to continue from morning to evening without any necessity of withdrawing before his accustomed hours to the necessities of nature.

How able he was to endure labor, how patient. Able through his spare diet to continue from morning to evening without any necessity of withdrawing before his accustomed hours to the necessities of nature.

![]() His uniformity and constancy in matter of friendship. How he would bear with them that with all boldness and liberty opposed his opinions, and even rejoiced if any man could better advise him. Lastly, how religious he was without superstition.

His uniformity and constancy in matter of friendship. How he would bear with them that with all boldness and liberty opposed his opinions, and even rejoiced if any man could better advise him. Lastly, how religious he was without superstition.

![]() All these things of him remember, that whenever your last hour shall come upon you, it may find you, as it did him, ready for it in the possession of a good conscience.

All these things of him remember, that whenever your last hour shall come upon you, it may find you, as it did him, ready for it in the possession of a good conscience.

![]() Stir up your mind, and recall your wits again from your natural dreams and visions, and when you are perfectly awakened, and can see that they were only dreams that troubled you; as one newly awakened out of another kind of sleep, look at these worldly things with the same mind as you did at those that you saw in your sleep.

Stir up your mind, and recall your wits again from your natural dreams and visions, and when you are perfectly awakened, and can see that they were only dreams that troubled you; as one newly awakened out of another kind of sleep, look at these worldly things with the same mind as you did at those that you saw in your sleep.

![]() I consist of body and soul. To my body all things are indifferent, for of itself it can't affect one thing more than another with apprehension of any difference; as for my mind, all things which are not within the verge of her own operation, are indifferent to her, and for her own operations, those altogether depend of her. Neither does she busy herself about any but those that are present, for as for future and past operations, those also are now at this present indifferent to her.

I consist of body and soul. To my body all things are indifferent, for of itself it can't affect one thing more than another with apprehension of any difference; as for my mind, all things which are not within the verge of her own operation, are indifferent to her, and for her own operations, those altogether depend of her. Neither does she busy herself about any but those that are present, for as for future and past operations, those also are now at this present indifferent to her.

![]() As long as the foot does that which belongs to it to do, and the hand that which belongs to it, their labor, whatever it is, isn't unnatural. So as long as a man does that which is proper for a man, his labor cannot be against nature; and if it isn't against nature, then neither is it harmful to him.

As long as the foot does that which belongs to it to do, and the hand that which belongs to it, their labor, whatever it is, isn't unnatural. So as long as a man does that which is proper for a man, his labor cannot be against nature; and if it isn't against nature, then neither is it harmful to him.

![]() But if it were so that happiness consisted in pleasure, how is it that notorious robbers, impure abominable livers, parricides, and tyrants, in so large a measure have pleasures?

But if it were so that happiness consisted in pleasure, how is it that notorious robbers, impure abominable livers, parricides, and tyrants, in so large a measure have pleasures?

![]() Don't you see how even those that profess the arts of a mechanic are in some respect no better than mere idiots, yet they stick close to the course of their trade, neither can they find in their heart to decline from it? And isn't it a grievous thing that an architect, or a physician shall respect the course and mysteries of their profession, more than a man the proper course and condition of his own nature, reason, which is common to him and to the gods?

Don't you see how even those that profess the arts of a mechanic are in some respect no better than mere idiots, yet they stick close to the course of their trade, neither can they find in their heart to decline from it? And isn't it a grievous thing that an architect, or a physician shall respect the course and mysteries of their profession, more than a man the proper course and condition of his own nature, reason, which is common to him and to the gods?

![]() Asia, Europe-what are they but corners of the whole world, of which the whole sea is but as one drop, and the great Mount Athos but as a clod, as all present time is but as one point of eternity?

Asia, Europe-what are they but corners of the whole world, of which the whole sea is but as one drop, and the great Mount Athos but as a clod, as all present time is but as one point of eternity?

![]() All are petty things; all things that are soon altered, soon perished. And all things come from one beginning; either all severally and particularly deliberated and resolved upon by the general ruler and governor of all, or all by necessary consequence. So that the dreadful hiatus of a gaping lion, and all poison, and all harmful things, are only (as the thorn and the mire) the necessary consequences of goodly fair things. Therefore don't think of these as things as contrary to those which you greatly honor and respect, but consider in your mind the true fountain of everything.

All are petty things; all things that are soon altered, soon perished. And all things come from one beginning; either all severally and particularly deliberated and resolved upon by the general ruler and governor of all, or all by necessary consequence. So that the dreadful hiatus of a gaping lion, and all poison, and all harmful things, are only (as the thorn and the mire) the necessary consequences of goodly fair things. Therefore don't think of these as things as contrary to those which you greatly honor and respect, but consider in your mind the true fountain of everything.

![]() He that sees the things that exist now has seen all that either ever was or ever will be, for all things are of one kind; and all are like one another. Meditate often on the connection of all things in the world, and on the mutual relation that they have to one another. For all things are after a sort folded and involved, one within another, and by these means all agree well together. For one thing is consequent to another, by local motion, by natural hidden combination and agreement, and by substantial union, or reduction of all substances into one.

He that sees the things that exist now has seen all that either ever was or ever will be, for all things are of one kind; and all are like one another. Meditate often on the connection of all things in the world, and on the mutual relation that they have to one another. For all things are after a sort folded and involved, one within another, and by these means all agree well together. For one thing is consequent to another, by local motion, by natural hidden combination and agreement, and by substantial union, or reduction of all substances into one.

![]() Fit and accommodate yourself to that state and to those occurrences which destiny has annexed to you, and love those men whom your fate it is to live with, but love them truly. An instrument, a tool, a utensil, whatever it is, if it's fit for the purpose it was made for, it is as it should be, though whoever made and fitted it is out of sight and gone.

Fit and accommodate yourself to that state and to those occurrences which destiny has annexed to you, and love those men whom your fate it is to live with, but love them truly. An instrument, a tool, a utensil, whatever it is, if it's fit for the purpose it was made for, it is as it should be, though whoever made and fitted it is out of sight and gone.

![]() But in natural things, that power which has framed and fitted them, abides within them still; for which reason she ought also the more to be respected, and we are the more obliged (if we may live and pass our time according to her purpose and intention) to think that all is well with us, and according to our own minds. After this manner also, and in this respect it is, that he that is all in all enjoys his happiness.

But in natural things, that power which has framed and fitted them, abides within them still; for which reason she ought also the more to be respected, and we are the more obliged (if we may live and pass our time according to her purpose and intention) to think that all is well with us, and according to our own minds. After this manner also, and in this respect it is, that he that is all in all enjoys his happiness.

![]() Whatever things are not within your proper power and jurisdiction will either encompass or avoid you, if you will propose to yourself any of those things as either good, or evil. It must be that according as you will, either fall into that which you think evil, or miss that which you think good, so will you be ready both to complain of the gods, and to hate those men, who either shall be so indeed, or shall by your be suspected as the cause either of your missing of the one, or falling into the other.

Whatever things are not within your proper power and jurisdiction will either encompass or avoid you, if you will propose to yourself any of those things as either good, or evil. It must be that according as you will, either fall into that which you think evil, or miss that which you think good, so will you be ready both to complain of the gods, and to hate those men, who either shall be so indeed, or shall by your be suspected as the cause either of your missing of the one, or falling into the other.

![]() And indeed we must commit many evils if we incline to any of these things, more or less, with an opinion of any difference. But if we mind and fancy only those things as good and bad which wholly depend of our own wills, there is no more occasion why we should either murmur against the gods, or be at enmity with any man.

And indeed we must commit many evils if we incline to any of these things, more or less, with an opinion of any difference. But if we mind and fancy only those things as good and bad which wholly depend of our own wills, there is no more occasion why we should either murmur against the gods, or be at enmity with any man.

![]() We all work to one effect, some willingly, and with a rational apprehension of what we do, others without any such knowledge. As I think Heraclitus, in one place, speaks of them that sleep, that even they do work in their kind, and confer to the general operations of the world.

We all work to one effect, some willingly, and with a rational apprehension of what we do, others without any such knowledge. As I think Heraclitus, in one place, speaks of them that sleep, that even they do work in their kind, and confer to the general operations of the world.

![]() One man therefore co-operates after one sort, and another after another sort; but even he that murmurs, and resists and hinders; even he as much as any cooperates. For the world also stood in need of such.

One man therefore co-operates after one sort, and another after another sort; but even he that murmurs, and resists and hinders; even he as much as any cooperates. For the world also stood in need of such.

![]() Now consider which among these you will rank yourself. For as for him who is the Administrator of all, he will make good use of you whether you want to or not, and make you (as a part and member of the whole) cooperate with him, that whatever you do shall turn to the furtherance of his own counsels and resolutions.

Now consider which among these you will rank yourself. For as for him who is the Administrator of all, he will make good use of you whether you want to or not, and make you (as a part and member of the whole) cooperate with him, that whatever you do shall turn to the furtherance of his own counsels and resolutions.

![]() But don't be ashamed of such a part of the whole, as that vile and ridiculous verse (which Chrysippus in one place mentions) is a part of the comedy.

But don't be ashamed of such a part of the whole, as that vile and ridiculous verse (which Chrysippus in one place mentions) is a part of the comedy.

![]() Does either the sun take it upon himself to do that which belongs to the rain? Or his son Aesculapius that to which the earth properly belongs? How is it with every one of the stars in particular? Though they all differ one from another, and have their several charges and functions by themselves, do they not all nevertheless concur and cooperate to one end?

Does either the sun take it upon himself to do that which belongs to the rain? Or his son Aesculapius that to which the earth properly belongs? How is it with every one of the stars in particular? Though they all differ one from another, and have their several charges and functions by themselves, do they not all nevertheless concur and cooperate to one end?

![]() If the gods have deliberated in particular of those things that should happen to me, I must stand to their deliberation as discrete and wise. For that a God should be an imprudent God is a thing that's hard to imagine—why should they resolve to do me harm? For what profit either to them or the universe (which they specially take care for) could arise from it?

If the gods have deliberated in particular of those things that should happen to me, I must stand to their deliberation as discrete and wise. For that a God should be an imprudent God is a thing that's hard to imagine—why should they resolve to do me harm? For what profit either to them or the universe (which they specially take care for) could arise from it?

![]() But if it is that they have not deliberated of me in particular, certainly they have of the whole in general, and those things which in consequence and coherence of this general deliberation happen to me in particular, I am bound to embrace and accept.

But if it is that they have not deliberated of me in particular, certainly they have of the whole in general, and those things which in consequence and coherence of this general deliberation happen to me in particular, I am bound to embrace and accept.

![]() But if it is that they have not deliberated at all (which indeed is very irreligious for any man to believe, for then let us neither sacrifice, nor pray, nor respect our oaths, neither let us any more use any of those things which we persuaded of the presence and secret conversation of the gods among us, daily use and practice) but, I say, if it is that they have not indeed either in general, or particular deliberated of any of those things that happen to us in this world. Yet God be thanked for those things that concern myself, it is lawful for me to deliberate myself, and all my deliberation is but concerning that which may be to me most profitable.

But if it is that they have not deliberated at all (which indeed is very irreligious for any man to believe, for then let us neither sacrifice, nor pray, nor respect our oaths, neither let us any more use any of those things which we persuaded of the presence and secret conversation of the gods among us, daily use and practice) but, I say, if it is that they have not indeed either in general, or particular deliberated of any of those things that happen to us in this world. Yet God be thanked for those things that concern myself, it is lawful for me to deliberate myself, and all my deliberation is but concerning that which may be to me most profitable.

![]() Now that is most profitable to every one which is according to his own constitution and nature. And my nature is to be rational in all my actions and as a good and natural member of a city and commonwealth towards my fellow members ever to be sociably and kindly disposed and affected. As I am Antoninus, my city and country is Rome; as a man, the whole world. Those things therefore that are expedient and profitable to those cities, are the only things that are good and expedient for me.

Now that is most profitable to every one which is according to his own constitution and nature. And my nature is to be rational in all my actions and as a good and natural member of a city and commonwealth towards my fellow members ever to be sociably and kindly disposed and affected. As I am Antoninus, my city and country is Rome; as a man, the whole world. Those things therefore that are expedient and profitable to those cities, are the only things that are good and expedient for me.

![]() Whatever in any kind happens to anyone is expedient to the whole. And therefore, much to make us content might suffice, that it is expedient for the whole in general. But yet this also will you generally perceive, if you diligently take heed, that whatever happens to any one man or men... And now I am content that the word expedient, should more generally be understood of those things which we otherwise call middle things, or things indifferent; as health, wealth, and the like.

Whatever in any kind happens to anyone is expedient to the whole. And therefore, much to make us content might suffice, that it is expedient for the whole in general. But yet this also will you generally perceive, if you diligently take heed, that whatever happens to any one man or men... And now I am content that the word expedient, should more generally be understood of those things which we otherwise call middle things, or things indifferent; as health, wealth, and the like.

![]() When you're presented with the ordinary shows of the theater and of other such places, they affect you as the same things still seen, and in the same fashion, make the sight ungrateful and tedious; so must all the things that we see all our life long affect us. For all things, above and below, are still the same, and from the same causes. When, then, will there be an end?

When you're presented with the ordinary shows of the theater and of other such places, they affect you as the same things still seen, and in the same fashion, make the sight ungrateful and tedious; so must all the things that we see all our life long affect us. For all things, above and below, are still the same, and from the same causes. When, then, will there be an end?

![]() Let the several deaths of all sorts men, and of all sorts of professions, and of all sort of nations, be a perpetual object of your thoughts, so that you may even come down to Philistio, Phoebus, and Origanion. Pass now to other generations. There, after many changes of all sorts, where so many brave orators are; where so many grave philosophers; Heraclitus, Pythagoras, Socrates. Where so many heroes of the old times; and then so many brave captains of the latter times; and so many kings.

Let the several deaths of all sorts men, and of all sorts of professions, and of all sort of nations, be a perpetual object of your thoughts, so that you may even come down to Philistio, Phoebus, and Origanion. Pass now to other generations. There, after many changes of all sorts, where so many brave orators are; where so many grave philosophers; Heraclitus, Pythagoras, Socrates. Where so many heroes of the old times; and then so many brave captains of the latter times; and so many kings.

![]() After all these, where Eudoxus, Hipparchus, Archimedes; where so many other sharp, generous, industrious, subtle, peremptory dispositions; and among others, even they, that have been the greatest scoffers and deriders of the frailty and brevity of this our human life; as Menippus, and others, as many as there have been such as he.

After all these, where Eudoxus, Hipparchus, Archimedes; where so many other sharp, generous, industrious, subtle, peremptory dispositions; and among others, even they, that have been the greatest scoffers and deriders of the frailty and brevity of this our human life; as Menippus, and others, as many as there have been such as he.

![]() Of all these, consider that they are all long since dead and gone. And what do they suffer by it? No, they that have not so much as a name remaining, what are they the worse for it? One thing there is, and that only, which is worth our while in this world, and ought by us much to be esteemed; and that is, according to truth and righteousness, meekly and lovingly to converse with false, and unrighteous men.

Of all these, consider that they are all long since dead and gone. And what do they suffer by it? No, they that have not so much as a name remaining, what are they the worse for it? One thing there is, and that only, which is worth our while in this world, and ought by us much to be esteemed; and that is, according to truth and righteousness, meekly and lovingly to converse with false, and unrighteous men.

![]() When you want to comfort and cheer yourself, call to mind the several gifts and virtues of those who you converse with daily. For example, the industry of the one, the modesty of another, the liberality of a third, of another some other thing. For nothing can so much rejoice you as the resemblances and parallels of several virtues, visible and eminent in the dispositions of those who live with you. Especially when all at once, as near as may be, they represent themselves to you. And therefore you must have them always in a readiness.

When you want to comfort and cheer yourself, call to mind the several gifts and virtues of those who you converse with daily. For example, the industry of the one, the modesty of another, the liberality of a third, of another some other thing. For nothing can so much rejoice you as the resemblances and parallels of several virtues, visible and eminent in the dispositions of those who live with you. Especially when all at once, as near as may be, they represent themselves to you. And therefore you must have them always in a readiness.

![]() Do you grieve that you only weigh but so many pounds, and rather not three hundred? Just as much reason have you to grieve that you must live but so many years, and not longer. For as for bulk and substance you content yourself with that proportion of it that is allotted to you, so you should for time.

Do you grieve that you only weigh but so many pounds, and rather not three hundred? Just as much reason have you to grieve that you must live but so many years, and not longer. For as for bulk and substance you content yourself with that proportion of it that is allotted to you, so you should for time.

![]() Let us endeavor most to persuade them, but if reason and justice lead you to it, do it, though they're never so much against it. But if any shall by force withstand you, and hinder you in it, convert your virtuous inclination from one object to another, from justice to contented equanimity, and cheerful patience: so that what in the one is your hindrance, you may make use of it for the exercise of another virtue and remember that it was with due exception, and reservation, that you inclined and desired at first.

Let us endeavor most to persuade them, but if reason and justice lead you to it, do it, though they're never so much against it. But if any shall by force withstand you, and hinder you in it, convert your virtuous inclination from one object to another, from justice to contented equanimity, and cheerful patience: so that what in the one is your hindrance, you may make use of it for the exercise of another virtue and remember that it was with due exception, and reservation, that you inclined and desired at first.

![]() For you didn't set your mind on impossible things. Upon what then? That all your desires might ever be moderated with this due kind of reservation. And this you have, and may always obtain, whether the thing is desired be in your power or not. And what do I care for more, if that for which I was born and brought forth into the world (to rule all my desires with reason and discretion) may be?

For you didn't set your mind on impossible things. Upon what then? That all your desires might ever be moderated with this due kind of reservation. And this you have, and may always obtain, whether the thing is desired be in your power or not. And what do I care for more, if that for which I was born and brought forth into the world (to rule all my desires with reason and discretion) may be?

![]() The ambitious suppose that another man's act, praise and applause, to be his own happiness; the voluptuous his own sense and feeling; but he that is wise, his own action.

The ambitious suppose that another man's act, praise and applause, to be his own happiness; the voluptuous his own sense and feeling; but he that is wise, his own action.

![]() It is absolutely in your power to exclude all manner of conceit and opinion, as concerning this matter; and by the same means, to exclude all grief and sorrow from your soul. For as for the things and objects themselves, they of themselves have no such power, whereby to beget and force upon us any opinion at all.

It is absolutely in your power to exclude all manner of conceit and opinion, as concerning this matter; and by the same means, to exclude all grief and sorrow from your soul. For as for the things and objects themselves, they of themselves have no such power, whereby to beget and force upon us any opinion at all.

![]() Use yourself when any man speaks to you so as to hearken to him, so that in the interim you don't give way to any other thoughts; that so you may as far as is possible seem fixed and fastened to his very soul, whoever he is that speaks to you.

Use yourself when any man speaks to you so as to hearken to him, so that in the interim you don't give way to any other thoughts; that so you may as far as is possible seem fixed and fastened to his very soul, whoever he is that speaks to you.

![]() That which is not good for the beehive can't be good for the bee.

That which is not good for the beehive can't be good for the bee.

![]() Will either passengers or patients find fault and complain, either one if he is well transported, or the others if well cured? Do they take care for any more than this; the one, that their shipmaster may bring them safe to land, and the other, that their physician may cause their recovery?

Will either passengers or patients find fault and complain, either one if he is well transported, or the others if well cured? Do they take care for any more than this; the one, that their shipmaster may bring them safe to land, and the other, that their physician may cause their recovery?

![]() How many of them who came into the world at the same time as I did are already gone out of it?

How many of them who came into the world at the same time as I did are already gone out of it?

![]() To them that are sick of the jaundice, honey seems bitter; and to them that are bitten by a mad dog, the water terrible; and to children, a little ball seems a fine thing. And why then should I be angry? Or do I think that error and false opinion is less powerful to make men transgress, than either cholera, being immoderate and excessive, to cause the jaundice; or poison, to cause rage?

To them that are sick of the jaundice, honey seems bitter; and to them that are bitten by a mad dog, the water terrible; and to children, a little ball seems a fine thing. And why then should I be angry? Or do I think that error and false opinion is less powerful to make men transgress, than either cholera, being immoderate and excessive, to cause the jaundice; or poison, to cause rage?

![]() No man can hinder you from living as your nature requires. Nothing can happen to you but what the common good of nature requires.

No man can hinder you from living as your nature requires. Nothing can happen to you but what the common good of nature requires.

![]() What manner of men they are who seek to please, and what to get, and by what actions: how soon time will cover and bury all things, and how many it has already buried!

What manner of men they are who seek to please, and what to get, and by what actions: how soon time will cover and bury all things, and how many it has already buried!

| Chapter 5 | Chapter 7 |